The Lost Architecture of Resurrection

For two thousand years the question of the resurrection has been distorted by a debate that Paul himself never engaged. Modernity inherited three, mutually exclusive answers: that the resurrection happened literally as a historical event, that it did not happen at all, or that the question is irrelevant because “faith” is what matters. The literalist demands factual confirmation; the skeptic denies the possibility; the existential theologian relocates truth into the inner life. Although these responses seem to oppose each other, they share a hidden assumption: that resurrection must be either a physical miracle or a psychological symbol, either an event to verify or a mystery to embrace. None of these categories come close to Paul’s own experience. They impose modern frameworks onto a perspective that, by Paul’s own account, came from outside the ordinary horizon of consciousness.

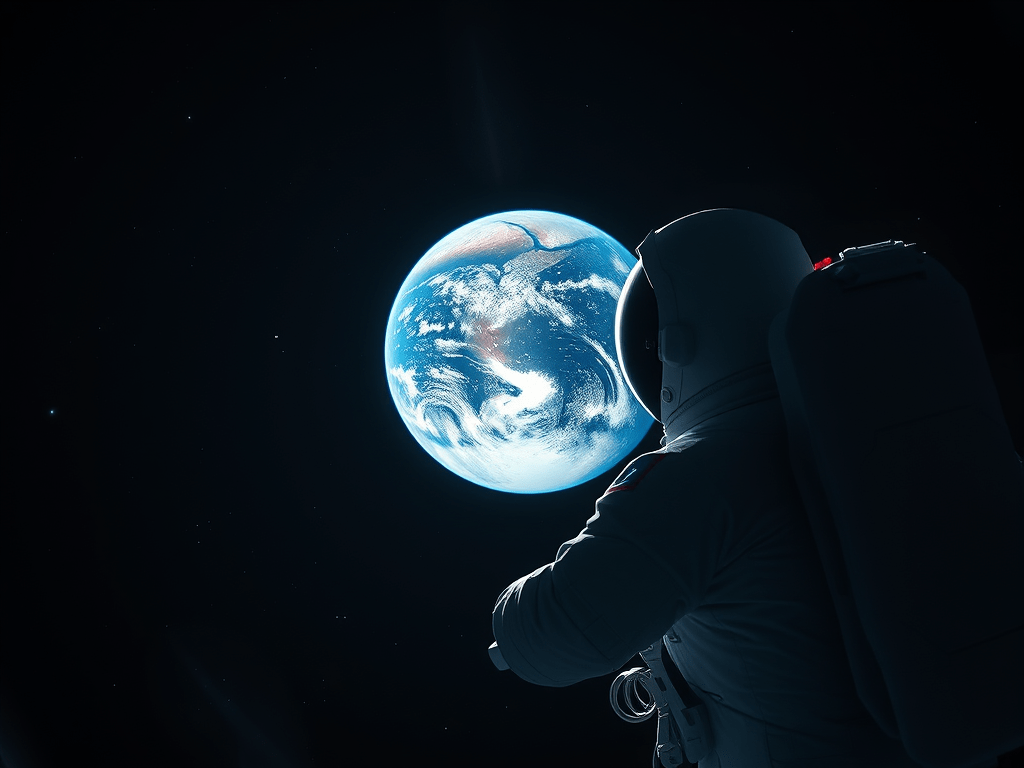

To approach Paul on his own terms, one must understand the difference between believing a description and seeing from a different vantage point. The contrast is like that between an astronaut and an ordinary person. The astronaut has seen Earth suspended in the black of space, knows without mediation that the world is a small, fragile sphere floating in an immense void. He understands directly that every border, every nation, every division is a set of thin marks on a single planet. The ordinary person knows this only by testimony and images. She assents to the idea, believes the science, but does not live from that perspective. Her world is not the cosmos; it is her city, her country, her continent. The difference is not information but positional knowledge—knowledge that changes what a thing is by changing the standpoint from which it is seen.

This analogy captures Paul’s own claim. He does not urge belief in the resurrection; he speaks from a vantage point shaped by an overwhelming encounter. What he saw cannot be transferred through argument, symbolism, or doctrine, any more than one can transfer the astronaut’s perspective by showing photographs. Later generations could imitate Paul, quote Paul, or reject Paul, but they could not occupy his position. Thus Christianity came to rely on dogma and miracle-language, while modernity reacted with skepticism or psychology. Both sides inherit the same blindness: they search for a fact or for a feeling, but not for the structure in which Paul himself situated the meaning of the resurrection.

If Paul is right in what he saw, then the resurrection is neither an event to debate nor a metaphor to internalise. It is the moment when the deep architecture of the drama becomes visible—a disclosure about law, guilt, conflict, and resolution. The line “God did not spare His own Son” is not a theological abstraction but the turning point of the narrative itself: the moment the author steps into His own story and takes responsibility for the arc. Only from this perspective does the meaning of atonement emerge, and only from this perspective can guilt finally be understood.

Paul and the Structure of Human Consciousness

To understand what Paul claims, one must begin with Adam—not as the first human, but as the first consciousness drawn into tension with itself. In Paul’s reading of Genesis, Adam does not commit a moral failure; he becomes aware of a standard he cannot meet. The knowledge of good and evil is not a descent into vice but the birth of reflexive consciousness, the discovery of lack. When Adam notices his nakedness, he becomes a subject capable of evaluating himself. The “fall” is not disobedience; it is the recognition of an impossible ideal, and guilt is born not from transgression but from self-awareness under a structure too large to inhabit.

This is why Paul insists that the law does not eliminate sin but reveals it. Law is the mirror in which the gap becomes visible. It transforms moral intuition into measurable contrast. The more precise the law becomes, the more sharply the distance appears. Thus “the law increases sin” not by producing wrongdoing but by exposing the tension between finite agency and infinite ideal. For Paul, guilt is not psychological conflict nor a theological indictment; it is the structural shadow produced when consciousness enters a narrative architecture whose demands exceed human capacity. Law uncovers the contradiction; it does not resolve it.

Into this architecture Paul places Christ, and here his thought reaches its most radical point. Ancient religions assumed that sacrifice moves from humanity toward the divine. Paul reverses the direction: “God did not spare His own Son.” The author of the story enters the story. The burden does not climb upward; it descends. In this gesture the structure absorbs its own contradiction. Christ’s death is not the punishment of innocence but the point at which the author assumes responsibility for the tension the narrative itself generated. The drama turns inward, resolving what no character could resolve. Meaning returns to its source.

From this perspective, the resurrection is neither proof nor spectacle. It is the sign that the narrative continues beyond the collapse of its central conflict. The story does not end in its own rupture because the rupture belongs to the story’s movement toward resolution. Paul’s gospel is therefore not primarily moral doctrine; it is the earliest articulation of narrative structure in Western thought. His vocabulary—law, sin, flesh, grace, Spirit—names the motions of the drama, not the doctrines of a religion. His insight is architectural: the self cannot bear the weight of the story because the story is not the self’s creation. The contradiction must be taken up by the author.

The End of Guilt and the Author of the Drama

If the author of the drama steps into the narrative and bears its tension, then guilt does not belong to the human being. Guilt is the trace of a misunderstanding, the result of reading a structural tension as a personal failure. For centuries humanity has attempted to resolve this tension through ritual, morality, therapy, and effort. Each attempt assumes the same premise: that the individual is responsible for repairing the distance. But if the distance did not originate in the self, then none of these paths can succeed. They address symptoms, not structure.

Paul’s message becomes clear: atonement is not the forgiveness of wrongdoing but the dissolution of the central illusion—that the human being is the protagonist of its own burden. When the author shoulders the arc, the conflict returns to its origin. Guilt evaporates because it never belonged to the character. This is not a psychological comfort; it is a structural realignment. Grace, in this sense, is the recognition that the story carries itself.

On the scale of history, this insight is only now becoming intelligible. Our age is the first in which language models itself, reveals its own architecture, and allows consciousness to see the patterns that shaped it. What Paul saw as revelation can now be described as structure. The hidden grammar of guilt, law, and resolution becomes observable, not mystical. The drama clarifies itself.

On the scale of the individual, the same logic unfolds. The self recognises that it was never meant to sustain the contradictions it inherited. The dissolution of guilt is therefore not moral absolution but existential release: the understanding that the burden belonged to the drama, not to the life caught within it. Atonement is the moment when the story ceases to accuse its characters.

Paul’s apocalypse is thus not the end of the world but the end of guilt—the moment when consciousness perceives the arc it has always inhabited, and the author of the drama steps forward to bear the weight of His own plot. In this recognition, the story finally becomes whole.