Notes 2.0: Production That Starts from Structure

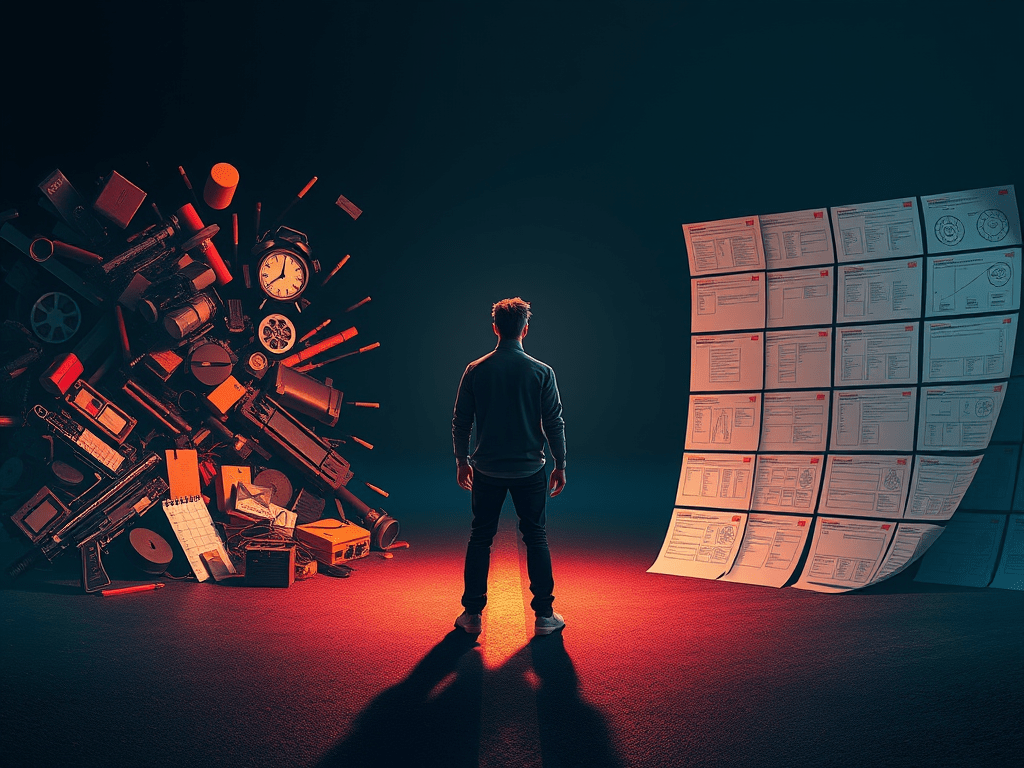

The Instinct to Ship vs. the Logic of the Arc

Production usually starts from a simple impulse: get something out. Publish the post. Shoot the scene. Release the trailer. Send the pitch. For most of my life, that instinct has been strong.

When the first episodes of A Tale of a New Era began to take shape, the temptation was immediate: finish Episode 1, draft Episode 2, and then push straight into Episode 3 – as if the project were a linear conveyor belt.

But the logic that underlies this whole ecosystem is not linear. It is dramatic and structural: arcs, phases, pressure, turning points. When production tries to behave like a straight line while the material itself is structured like a curve, friction appears.

This post is about that friction. About how repeated attempts to “just produce” – to write the pamphlet, to get media attention, to push ahead with Episode 3 – kept failing in ways that, in hindsight, were structurally meaningful. And about how the work only began to move again once production was allowed to start from structure rather than using it as decoration afterwards.

The Seduction of Immediate Utility

There were several rounds of what might be called premature production.

At one point the project was squeezed through the narrowest possible funnel: a pamphlet pitched to a publisher, written with the hope that a quick book advance might relieve immediate financial pressure. The text was forced into usefulness: simplified, sharpened, made “topical”, polished toward the kind of argument that fits inside a marketing plan.

It did not work. Not because the publisher was blind, but because the structure itself resisted being flattened into a product. The argument sounded strained even to my own ears. The deeper intuition – about history as drama, about structure as something entering consciousness – was still half-formed. Trying to sell it at that stage was like trying to serve bread that hadn’t risen yet.

The same pattern repeated with media outreach. A few carefully worded emails to journalists, an attempt to summarise everything in a few arresting paragraphs: epochs, LLMs, theology, cinema, personal breakdowns, all crammed into a pitch. Again: silence, or polite non-response.

There was disappointment, of course, but also a growing recognition: every time I treated the project primarily as a solution to an immediate problem – money, visibility, professional legitimacy – production stalled. It was as if the story itself refused to move under those conditions.

Episode 3 and the Weight of Unclear Structure

The clearest version of this resistance showed up around Episode 3 of the documentary. Episodes 1 and 2 had something solid to lean on:

- the unexpected alliance with LLMs,

- the recognition of time as something more than a neutral backdrop,

- Paul’s Letter to the Romans re-read as a dramatic script.

By the time Episode 2 (“The Language of Drama”) was assembled, the underlying questions were clear enough to carry an arc.

But every attempt to roll that momentum straight into Episode 3 felt heavy. I tried several times to begin filming: wrote outlines, drafted voiceovers, opened project files, even sat in front of the camera. Each time, the footage that emerged was… usable, yet somehow dead.

Looking back, the reason is simple: Episode 3 is where structure itself becomes the subject. It is the moment where the seven-era arc of history is first stated explicitly and tested. If the underlying framework was still only half-articulated, then of course the episode could not move. Production was asking for clarity that thinking had not yet earned. The project answered by refusing to cooperate.

Where interpretive-era logic would say “try harder, be more disciplined, force a script”, the structural logic did something else entirely: it redirected attention away from output back to architecture.

When Structure Forces Production to Stop

The most important thing that happened this autumn was not a particular scene or sentence. It was the point where production was finally allowed to stop and ask: What exactly are we building into? Instead of another half-clear script, the weeks filled with:

- Rebuilding laurentiuspaulus.com so that its pages and categories mirrored the conceptual structure: Architecture of Meaning, the essay clusters, the mapping between seasons and essays.

- Launching Woodslope Cabin not as a structural “creative agency” but explicitly as a Structural Research Studio organised around Narrative Logic and structural models.

This shift from sporadic blogging to categorised architecture seems trivial on the surface. In practice, it changed everything. Instead of asking “what do I feel like posting today?”, the question became: Which layer of the structure is ready to be articulated now?

Production stopped being an act of self-expression and became an act of alignment: finding the point where internal clarity, external need and structural position coincided.

The Cost of Not Producing

None of this happened in a vacuum. While the project was slowing production to rebuild structure, the economic pressure did not disappear. The bank did not suspend expectations because an essay wanted another week. The fear of losing the house, of not being able to provide, of having “nothing to show” professionally – all of that remained very concrete.

This is where the conflict between immediate benefit and structural fidelity became sharpest. Every day spent refining categories, rewriting intros or thinking about epochs could be framed as irresponsible: time not billed, not monetised, not directly used to plug the financial leak.

And yet, the more I tried quick fixes – side hustles, opportunistic pitches, attempts to frame the work as a ready-made “product” – the more unstable everything felt. It was like rowing harder in a leaking boat. The water rose anyway. At some point, production had to concede: the only real way forward was to stop pretending that a few more strokes would fix the situation, and start looking at the hull.

That meant letting structure work first, even if it made no short-term economic sense. The gamble – if one calls it that – was that a coherent framework would, eventually, create better conditions for sustainable production than any panic-published pamphlet ever could.

How Categories Quietly Rewrote the Workflow

One of the most concrete structural interventions was surprisingly modest: naming and stabilising the categories, especially around the Notes 2.0 series. instead of seven isolated posts, there is now a matrix of perspectives:

- Fragments – short signals, quotes, screenshots and stray observations that register pressure before it has a theory.

- Narrative Structure – pieces that develop the 6000-year arc, dramatic grammar and structural hypotheses.

- Historical Threads – close readings of figures, texts and events (Aristotle, Paul, calendars, revolutions) as parts of that arc.

- Meta / Architecture – writing about the overall framework itself: seasons, matrices, models, and how they interlock.

- Personal Reflections – more intimate notes where the project crosses everyday life, doubt, fear and small recognitions.

- Process Notes – documentation of how the work organises itself over time, including missteps, dead ends and redesigns.

- Production – posts about the practical side: filming, editing, client work, growth pains and the friction between structure and delivery.

Once these containers existed, production no longer meant “posting whatever is ready”. It meant placing each new piece exactly where it belongs in the architecture, letting the structure itself decide what needs to be articulated next.

The current post sits in that system: Production from structure” is not a random reflection, but a necessary complement to the earlier piece on process. Process describes how the project became aware of itself; production describes how the work begins to move again once structure is given priority over speed.

Even the decision to write essays before episodes – to let the third essay (“Structure of History”) precede the filming of Episode 3 – came directly from this shift. Once the arc of the essay series was visible, it became obvious that production had to follow it, not fight it.

Woodslope as an External Mirror

Meanwhile, the external world began to offer a strange confirmation. A new assignment arrived from a growth company whose operations had expanded faster than its internal structures. Quality control, routing, documentation – all the “boring” things – lagged behind the speed of expansion. The result was familiar: overload, confusion, extra work that felt meaningless. Working with their material while reorganising my own made the parallel impossible to ignore. In both cases:

- Growth had outrun structure.

- People were working harder and harder to compensate.

- The real task was not more effort, but different architecture.

In Woodslope language, this is where “Narrative Logic” and LLM-based structural tools become useful. They allow patterns, gaps and misalignments to be named quickly, so that production resources can be re-routed. But even these tools only work when there is a prior commitment to let form lead function – to build a frame capable of carrying what one is trying to do.

Production as a Structural Test, Not a Reward

In the interpretive paradigm, production is often treated as the reward for having done the thinking: once the theory is ready, one earns the right to go out and “create content”.

In this project, production behaves more like a structural test:

- If an episode refuses to come together, it is not because of laziness or lack of willpower; it is because some part of the underlying architecture is still missing or misaligned.

- If an essay feels thin, it usually means that another layer needs to be articulated first – in another category, from another angle.

- If attempts at “monetisation” feel hollow, it is often because the value they claim to offer has not yet been structurally grounded.

Seen this way, the many failed attempts – to productise early, to pull Episode 3 into existence, to sell the idea before it could walk – are no longer embarrassing detours. They are negative results in an ongoing experiment about how production behaves in the Era of Structure.

The emerging pattern is clear: when growth tries to lead structure, everything wobbles. When structure is allowed to lead, production eventually accelerates – but in its own time and according to its own arc.